The Codex described

Codex A

The Codex Eyckensis consists of 133 folio’s, parchment leaves. The first part, Codex A, opens with a full page portrait of an Evangelist writing. In his right hand he holds a quill. A small inkwell is placed on the armrest of his seat. It is surmised that the portrait depicts the evangelist Matthew, because this miniature resembles the portrait of Matthew in another eighth-century manuscript; the Barberini Gospels currently kept in the Vatican Library (Barb. Lat. 570). The figure is rendered in Italian-Byzantine style. We know that Saint Willibrord brought Italian manuscripts to Echternach from his travels to Rome. Matthew is shown seated on a throne in a frame of Anglo-Saxon knotwork, which makes the miniature an outstanding blend of two European styles.

The Evangelist portrait is followed by four folios containing an incomplete set of Canon Tables, eight in all. Canon Tables provide an overview of corresponding passages in the four Gospels and as such are an important resource for anyone who wishes to study the Gospels in detail. They serve as table of contents and index to ease access to the texts. This system of Canon Tables was perfected by bishop Eusebius of Caesarea (3rd–4th century) and remained in use for several centuries, until the division of the Gospel texts into chapters (13th century) and verses (16th century) became more prevalent. The Canon Tables of Codex A are presented between five slender columns. These are topped with four round arches decorated with the Evangelists’ symbols; Matthew is symbolised by a man, Mark by a lion, Luke by an ox and John by an eagle. Two larger arches are drawn over the four arches with the Evangelist symbols and the whole is crowned by a large arch embellished with a portrait of a haloed saint.

Codex B

Codex B is somewhat more restrained than A: no beautiful portrait of Evangelists writing, fewer symbols... On the other hand there is a full set of twelve Canon Tables and the complete texts of the four Gospels. The Canon Tables of Codex B are written between three columns connected by two round arches, which are in turn crowned by a larger arch. Each of these large top arches is embellished with the portrait of an Apostle in an expressive blessing pose or with an Evangelist symbol. The capitals and columns are decorated with Anglo-Saxon knotwork. Some of the columns have bases with graceful Anglo-Saxon knotwork. Other columns are supported by mythical creatures. On these pages, the use of colour is also highly refined.

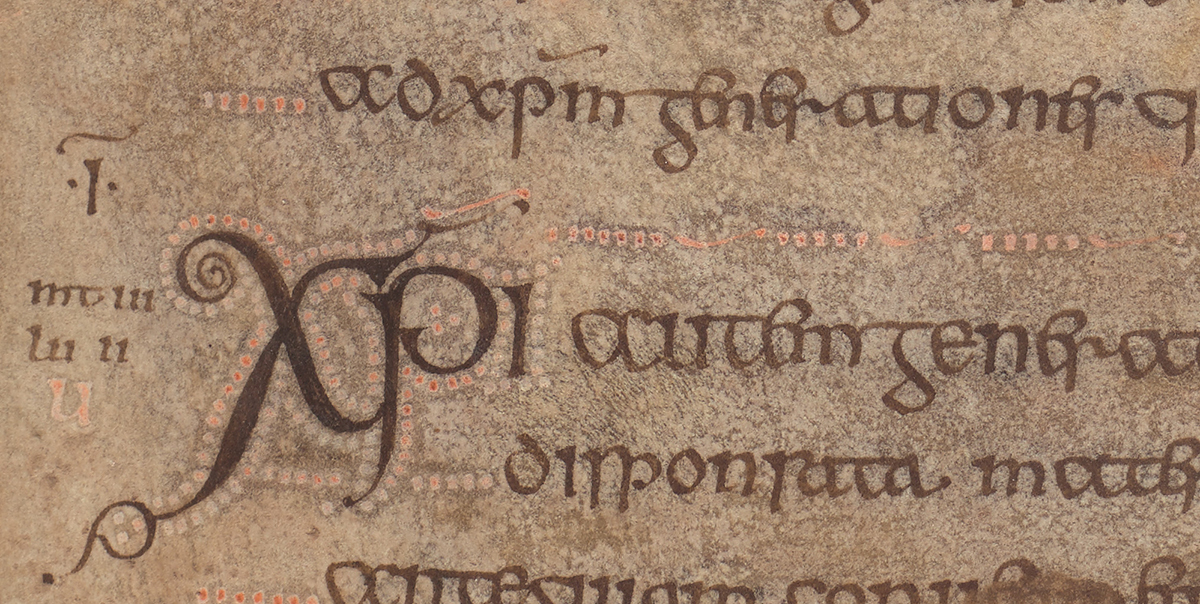

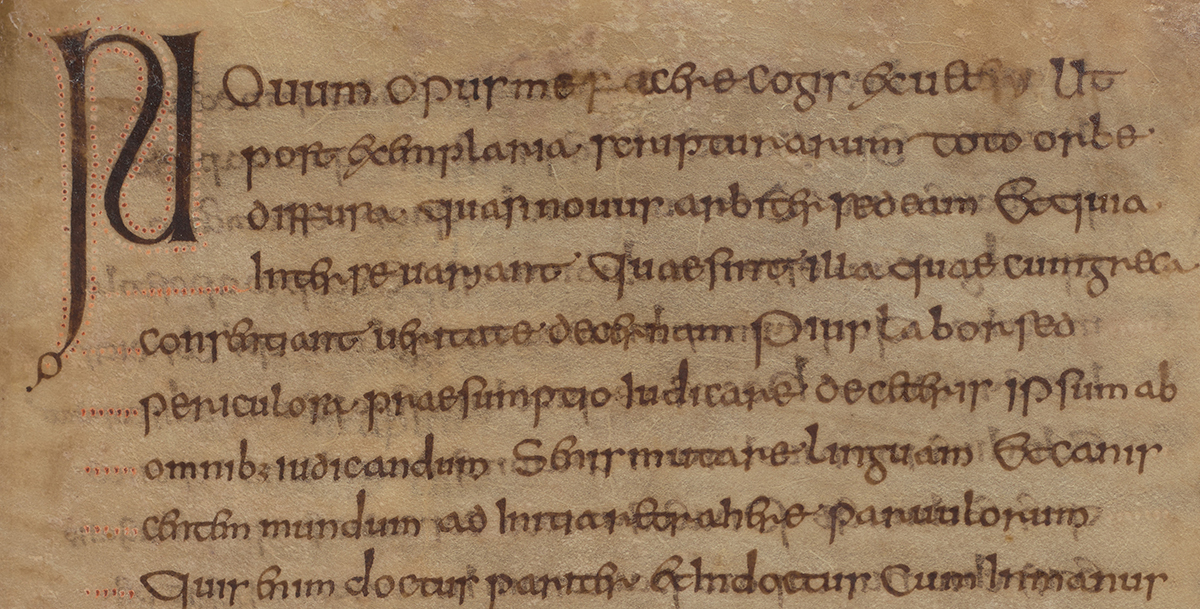

Similar refinement can be found on the folios with the Gospel texts. Each page has 26 lines of text in an insular script that is typical for the seventh- to eighth-century Hiberno-Saxon tradition. This style was also in fashion in scriptoria on the continent. The insular script used in the Codex Eyckensis is a little more rounded than that in the famous Book of Kells or the Lindisfarne Gospels. Important passages are marked with lines of red dots. The first letter of each paragraph is outlined in red and yellow dots—minor but effective measures to increase readability. Every sentence is accentuated with a graceful black initial capital.

Most likely in the course of the twelfth century codex A and codex B were merged and bound together. Codex A is the remainder of a precious illuminated Gospel manuscript that probably contained full-page portraits of all four Evangelists. However, only the portrait of Saint Matthew and the Canon Tables are now left. Whoever ordered both codices to be bound together must have had a good idea of their value and of the connection between them. For indeed, Codex A and B both date from the same period and it is even likely that both were made at the same scriptorium.

The Vulgate

The Gospel text in the Codex is a version of the Vulgate, which is the Latin translation of the four Gospels made by Saint Jerome (Hieronymus of Stridon, 347–420 CE). For one thousand years the Vulgate remained the predominant Bible translation. Even so, compared to Saint Jerome’s translation, the text of the Codex Eyckensis contains a number of additions and transpositions. Once again this can be traced to a Hiberno-Saxon model. Indeed, comparable Gospel texts can be found in the Book of Kells, the Book of Armagh and the Echternach Gospels.

Sparkling with gold and glistening with pearls

The biography of Saints Harlindis and Relindis, which was written a century after their deaths, tells us that the books of Aldeneik looked so bright and fabulously “sparkling with gold and pearls, that one could easily believe they had only been completed earlier today”. This may well have been an allusion to a treasure binding with gold and pearls. Unfortunately, if the manuscripts ever were protected by such opulent binding, nothing now remains of this.