Codex Eyckensis: The unique Codex of Eyke

The oldest book

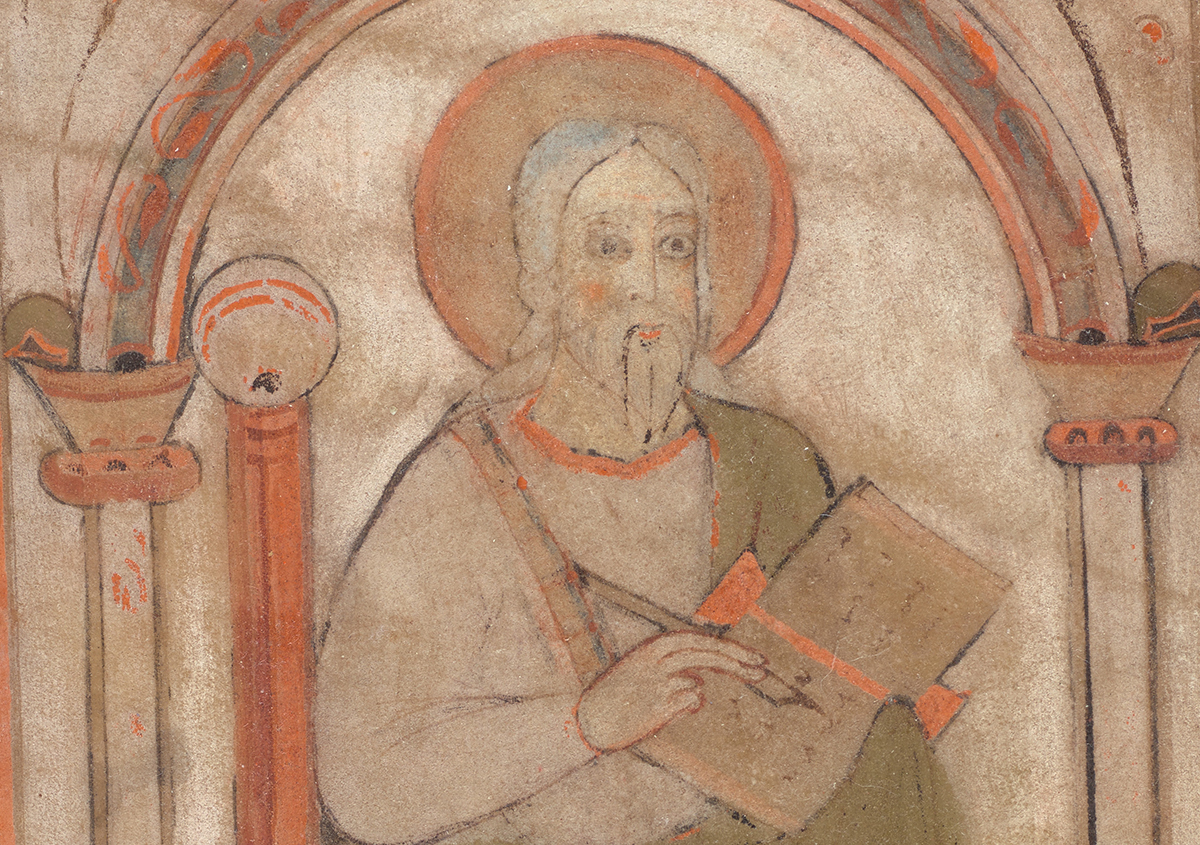

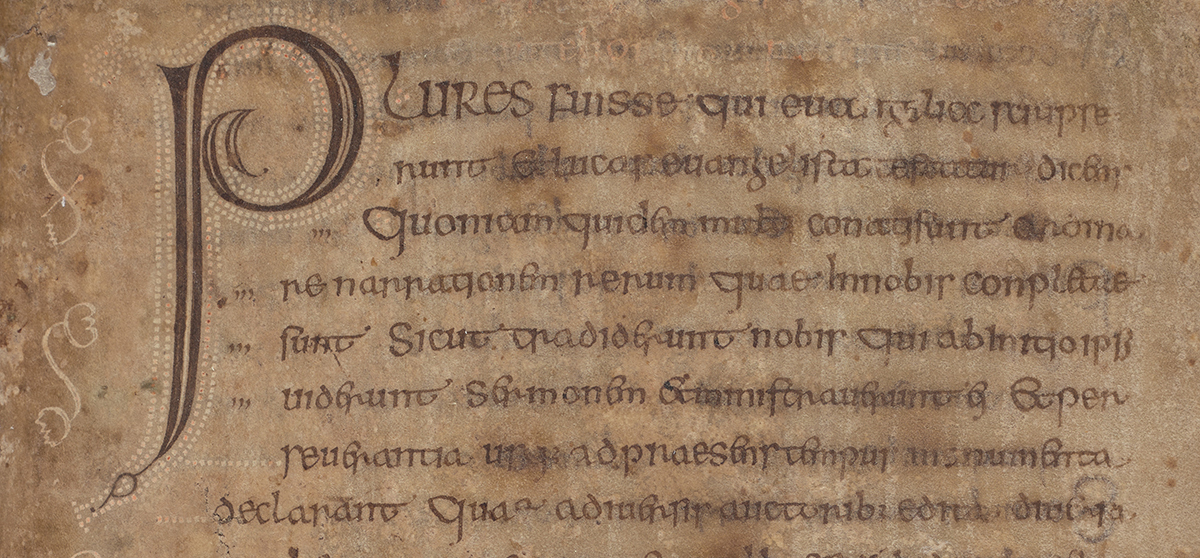

The Codex Eyckensis is Belgium’s oldest book. Moreover, it is the oldest Gospel Book of the Low Countries—present-day Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg. The Codex was written by hand on parchment by an eighth-century monk. The book consists of two parts. Codex A, the first part, is a fragment of a Gospel manuscript comprising the portrait of an Evangelist, depicted serenely writing, seated on a throne under an arc, framed within a beautiful knotwork border. The Evangelist portrait takes up one full folio. It is followed by four folios with Canon Tables: lists of corresponding sections in the four Gospels. This complex information is presented in an architectural frame of pillars and arches to assist the reader in locating and tracking concordant passages. These Canon Tables are incomplete. Codex B, the second part of the manuscript, does have a complete set of twelve Canon Tables. These Canon Tables are followed by the Gospels of Matthew, Marc, Luke and John. The two manuscripts were merged into one binding, most likely in the course of the twelfth century.

The fact that the manuscript is still kept at the original location is highly unusual. Equally remarkable is the continuing popular devotion to the saints for whom the Codex Eyckensis was originally intended, Harlindis and Relindis. The next 25-yearly procession in honour of the two saints is planned for the year 2022.

Prestigious provenance

The Codex dates back to the time of the Christianisation of Western Europe. Renowned missionaries such as Willibrord and Boniface came from Ireland and Britain to the Continent to spread Christianity. While the mainland had already been Christianised in the course of the third and fourth centuries, this process had been interrupted and even reversed by the influx of heathen Germanic tribes. Willibrord and Boniface succeeded in convincing the Merovingian rulers of the importance of their message, which in a political sense boiled down to: rejoin (papal) Rome.

Willibrord and Boniface founded a large number of Benedictine monasteries: centres of knowledge and of the “cult of the word”. Highly educated monks and nuns prepared parchment and produced pens, inks and pigments, aiming to copy out and reproduce rare texts as faithfully as possible. These were not only Bible texts, but also commentaries on such texts, written by the Fathers of the Church from the first centuries of Christianity. Each new monastery needed new books. Since 698 CE, Willibrord had set up his headquarters at the abbey of Echternach in Luxembourg. This abbey had its own professional scriptorium, where a great many manuscripts were produced and from there distributed all over the territories of present-day Luxembourg, Belgium and the Netherlands. The Codex Eyckensis was probably also one of these manuscripts produced in Echternach—a prestigious provenance indeed.

1200 years in Eyke

Since the eighth century the Codex Eyckensis has always been kept and preserved on the territory of the current municipality of Maaseik. In that sense, the book is doubly unique: it is not only the oldest book in Belgium, in addition it has been kept in the same municipality for over 1200 years. Two Merovingian nobles, Lord Adelard and his wife Grinuara, founded an abbey for their two daughters Harlindis and Relindis, in “a small and useless wood” on the banks of the river Meuse. They called this abbey "Eyke" (= oak), a simple reference to the kind of trees that grew there. Later, the name changed to Aldeneik (= Old Eyke). The sisters Harlindis and Relindis became the first and second abbesses of the convent, consecrated by Willibrord and Boniface, respectively. So there was this small community of religious women living at the abbey of Eyke, who needed books to be able to live and spread their faith in a fitting way. Probably Willibrord brought both parts of the Codex Eyckensis on his missionary travels from Echternach.

Later Harlindis and Relindis were both canonised and in the ninth century a local priest wrote a short biography of the sisters. This text contains a lot of local information. A little over one hundred years after their demise, it was told that they had received an excellent education in a French convent, where they had learnt calligraphy, painting, weaving and embroidery. In the biography, we also read that Harlindis and Relindis had written an evangelistary and a psalter. So from the ninth century tradition had it that the Codex Eyckensis was written by Saints Harlindis and Relindis personally. The faithful in Eyke honoured the memory of “their” saints and also venerated the precious relic they had left behind: the Codex.

An eventful history

The Codex Eyckensis has been kept and preserved in the same town for over 1200 years. In spite of that, its history has been rather eventful. In the ninth century, Saints Harlindis and Relindis were buried in sarcophagi in the new stone church that had been built by abbess Ava. The relics were venerated by the faithful, along with the Codex. In the year 952, emperor Otto I bestowed the abbey on the cathedral church of Liège. The former nunnery was made into a chapter with male canons. In the course of time a new settlement was established near Aldeneik, which was called Nieuw Eyke (“new Eyke”). Nieuw Eyke flourished and grew into the town of Maaseik, which was granted its borough charter in the year 1245. Later Aldeneik became a part of the municipality of Maaseik.

In the sixteenth century, religious war broke out in the Low Countries. In 1571, out of fear for marauding Calvinist army contingents, the canons left the unprotected rural village of Aldeneik. They sought protection within the town walls of Maaseik, taking the relics of Harlindis and Relindis with them. Since then, the relics have been kept in the Collegiate Church of Saint Catherine in Maaseik.

During the twentieth century the Codex Eyckensis did not suffer so much from war as from a failed conservation attempt. In 1957 the dean of Maaseik is thought to have taken the Codex Eyckensis in the pannier bag of his motorcycle all the way to Düsseldorf, where amateur restorer Karl Sievers then proceeded to laminate the folios with “Mipofolie” adhesive foil—a method that had been used to protect maps in the Second World War. This proved to be well-nigh disastrous. Between 1988 and 1992 this Mipofolie was removed from the parchment folios with painstaking care and using the most advanced methods. On this occasion the two constituent manuscripts, Codex A and Codex B, were separated and individually bound.

Since 1994 the Codex Eyckensis is once more on display as part of Saint Catherine’s Church treasure.